Wednesday marks 50 years since the completion of the CN Tower’s main construction — the day the Toronto landmark became the world’s tallest freestanding structure, a title it held for over three decades.

On that day, April 2, 1975, the city was abuzz in anticipation of the moment a helicopter known as “Olga” would slot the final piece of the $57-million tower’s antenna into place.

“Cut her loose.”

Those were the words rigger Paul Mitchell uttered from atop the CN Tower, confirming the job was complete.

Cheers rang out among the 300 people gathered in the observation gallery of the Toronto-Dominion Centre.

A red flare was shot off the 1,815-foot-high tower and the Canadian flag was unfurled. Office tower windows were filled with onlookers watching the moment, while traffic was halted below as drivers gazed upwards to do the same.

Asked later how he felt about the tower reaching its full height, design and construction director Malachy Grant said it was “Lucky. Just lucky. And glad we’d never done anything stupid, made no serious goofs.”

Indeed, over the two years that the tower was constructed, there were few errors, little labour strife, and only one fatality.

Aiming to improve the airwaves

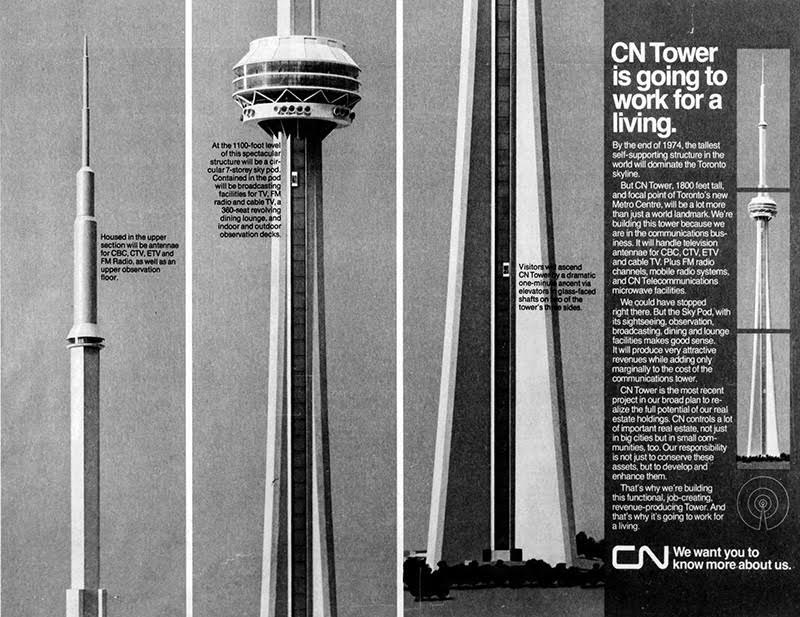

The CN Tower evolved out of CBC’s desire for stronger transmission, especially its television signal.

By the late 1960s, as commercial and residential towers grew across Toronto, viewers complained about worsening TV reception within the city. The network also wanted to improve its reception in nearby areas such as the Niagara Peninsula.

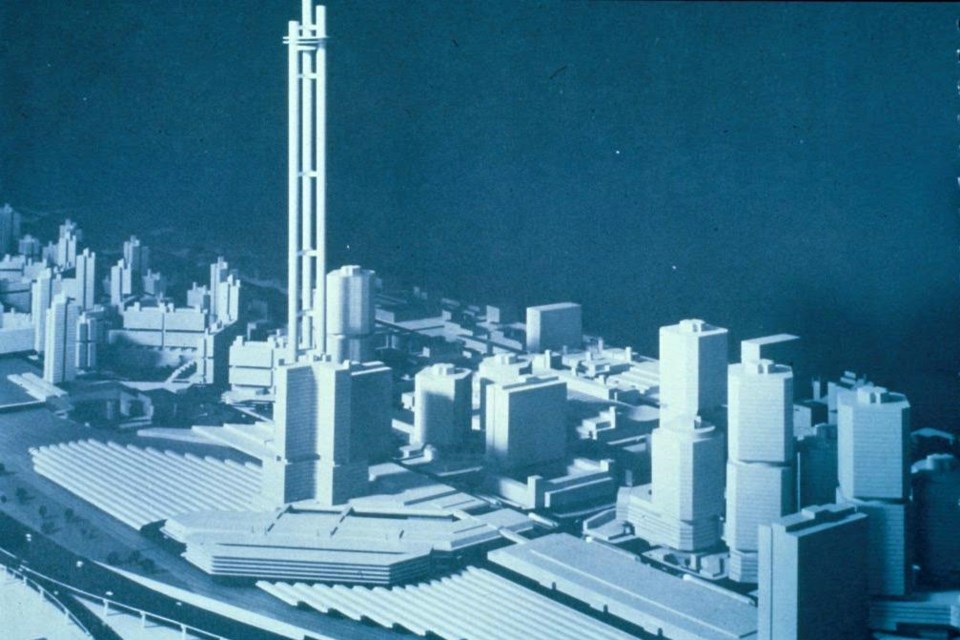

CBC approached Canadian National (CN) and Canadian Pacific (CP) railroad companies in 1967 to incorporate a transmitter into their plans for “Metro Centre,” a project that envisioned massive redevelopment of the railway lands south of King Street for employment, entertainment and residential use.

The original design for the tower, released in 1968, depicted three slim structures of varying heights connected by enclosed bridges. The complex would include a revolving restaurant and observation deck. CBC considered consolidating its local operations into a new broadcasting centre at the tower’s base. Under the Metro Centre proposal, the cost of the tower would have been split between CBC, CN and CP.

The plan quickly faced roadblocks. Funding cuts forced CBC to drop out of the project, though it would eventually build the current Canadian Broadcasting Centre complex on Front Street to the north.

Planning for Metro Centre stalled over the fate of Union Station, which wasn’t demolished as planned. Though the name faded, elements of Metro Centre, such as Roy Thomson Hall and the Toronto Convention Centre, were built.

When CP also backed out of the tower, CN carried on and the landmark became its namesake.

A revised design that consolidated the three sections into one tower was unveiled to the public on February 5, 1973.

“It has been a long arduous struggle to bring these plans to fruition,” then-premier Bill Davis observed, “But now those of us who live in Brampton will be able to look up and see downtown Toronto.”

David Crombie, the city’s mayor at the time, called it “a welcome addition to the Toronto skyline.”

Cue the backlash

As the project site was cleared, opposition arose.

Naturalists warned that during migration season over 1,000 birds per day could fatally fly into the tower (bird-sensitive lighting would be incorporated). Pilots worried about the potential for plane crashes and feared the tower would interfere with operations at the island airport.

A few city councillors saw these concerns as reasons to delay approvals at the Buildings and Development Committee.

Former alderman Elizabeth Eayrs warned the city “will live to regret its indecent haste to put up this monster thing.”

John Sewell, then a city councillor, added potential traffic chaos to his list of concerns but failed in his effort to cut the tower’s height in half to protect birds.

When the committee approved the project on June 11, Eayrs claimed it was “a finger point at the sky — a finger pointing in defiance of the gods above, whoever they may be.”

During the preparation stages, models of the towers were tested in a University of Western Ontario wind tunnel, demonstrating it could withstand winds of up to 418 km/h (260 miles/h).

Staff visited other tall structures around the world to avoid mistakes that had been made related to ice sheets and suicide prevention.

One valuable lesson they learned: copyright and trademark the tower to prevent revenue loss.

Just another construction gig

The tower rose speedily. Concrete was poured into a slipform that added around 20 feet (6 metres) of height daily between June 1973 and February 1974.

The slipform was adjusted hourly, as, beyond the core shaft, it was also used to form shafts for elevators and a stairway, as well as inserts for cables, heating and lighting.

Many site workers interviewed by the media in progress reports appeared to treat their work as just another construction job.

“Maybe once it becomes more obvious that we’re looking down on other buildings, there’ll be more excitement,” electrical superintendent Mike Bolan told the Toronto Star when the tower hit the milestone of surpassing the height of Commerce Court in September 1973.

Some took advantage of their unique work situation: signalman “Sweet William” Eustace grew sick of his job and decided to go out in a blaze of glory.

On November 8, 1974, he parachuted off the crane from the top of the tower, which was then 1,500 feet tall. On the way down, he nearly hit high voltage wires by the revolving restaurant.

After landing safely, he was fired for violating safety procedures and later fined $50 in court.

Only one fatality occurred during the build and it didn’t happen in the sky. Construction inspector John Ashton was standing at ground level when a wind gust ripped away a piece of plywood from a platform, striking Ashton in the head. The force threw him against the tower wall, breaking his neck.

Chopper time

During the final weeks of the tower’s main construction, a Sikorsky Skycrane helicopter nicknamed “Olga” was brought in from the United States to dismantle the crane piece-by-piece and place the antenna on top.

Olga’s first flight nearly ended in disaster when the crane, which was unevenly balanced, lurched forward with its operator inside. Supporting pins that had seized up had to be burned off, eating up valuable time.

By the time the crane boom was lifted off, Olga only had 14 minutes of fuel left.

As completion day neared, one of the final segments of the transmission mast was put on display at Harbourfront. School children were invited to sign the section with indelible pens. Over 7,000 signatures were inked.

Despite some early problems with ice, Olga performed its job well, finishing the antenna assembly process 10 days ahead of the initial schedule.

The CN Tower gets its crown

It took three attempts for the final antenna segment to be lowered on April 2, 1975.

Mitchell waited for over an hour on top of the tower amid high winds that complicated the insert, including one try where the antenna was slotted in backwards.

Once the mission was a success, Mitchell was joined on a small platform by four iron workers.

He danced a jig and waved to Olga as it sped off to fly around the official celebration at the TD Centre. The festivities were presided over by then-federal energy minister Donald Macdonald, who was also the tallest member of cabinet.

Later that night, workers partied at the Seaway Towers hotel on Lake Shore Boulevard. Globe and Mail reporter Christie Blatchford described the occasion as “mushy,” as attendees celebrated their achievement.

Further refinements were made over the next year, including adjusting the mast, before the CN Tower opened to the public in June 1976.

Those who worked on the project predicted that they would look back on it with pride. “When we’re all 85 and have canes,” Grant told Canadian Magazine in 1974, “we can point to it and cackle to our grandchildren ‘I was associated with that.’”